Benefits and Process of Oil-to-Gas Conversion

Introduction and Outline

Oil-to-gas conversion is about more than trading one fuel for another. It touches safety, local building codes, utility infrastructure, household budgets, and the bigger question of how we heat homes without overtaxing the climate. The appeal is clear: modern gas appliances tend to be compact, quiet, and capable of high efficiency, while the fuel often arrives via buried mains rather than trucks. That said, every property is different. Older homes may have chimneys that need relining, underground oil tanks that demand careful decommissioning, or hydronic systems that justify keeping a boiler rather than switching to a warm-air furnace. This article balances conversion mechanics, efficiency, and sustainability with practical examples and calculations, keeping marketing hype at arm’s length and centering what actually matters in day-to-day operation.

To set expectations, here is a quick map of where we are headed. Think of it like opening the toolbox before the job starts.

– Why conversion is on the table now: energy prices, equipment age, and policy trends

– The conversion process: assessment, gas service, equipment selection, venting, commissioning

– Efficiency in practice: AFUE, modulation, distribution losses, and controls

– Sustainability: CO2 factors, methane leakage, and future-ready choices

– Costs, incentives, and a decision checklist to close with clarity

Conversion merits a holistic look. A high-AFUE appliance can underperform if ductwork leaks, a beautifully piped boiler can short-cycle without right-sized controls, and a clean combustion plume still contributes to greenhouse gases if upstream methane is unmanaged. At the same time, leaving an aging oil system in place can mean lower efficiency, higher local pollutants, and rising maintenance bills. Our goal is to evaluate trade-offs transparently. You’ll find data points (for example, typical CO2 per unit energy and common AFUE ranges), realistic steps for planning the work, and ways to future-proof your heating so today’s investment stays useful as energy systems evolve. Let’s open the door, step into the mechanical room, and look around with a clear, methodical lens.

From Oil to Gas: The Conversion Process Step by Step

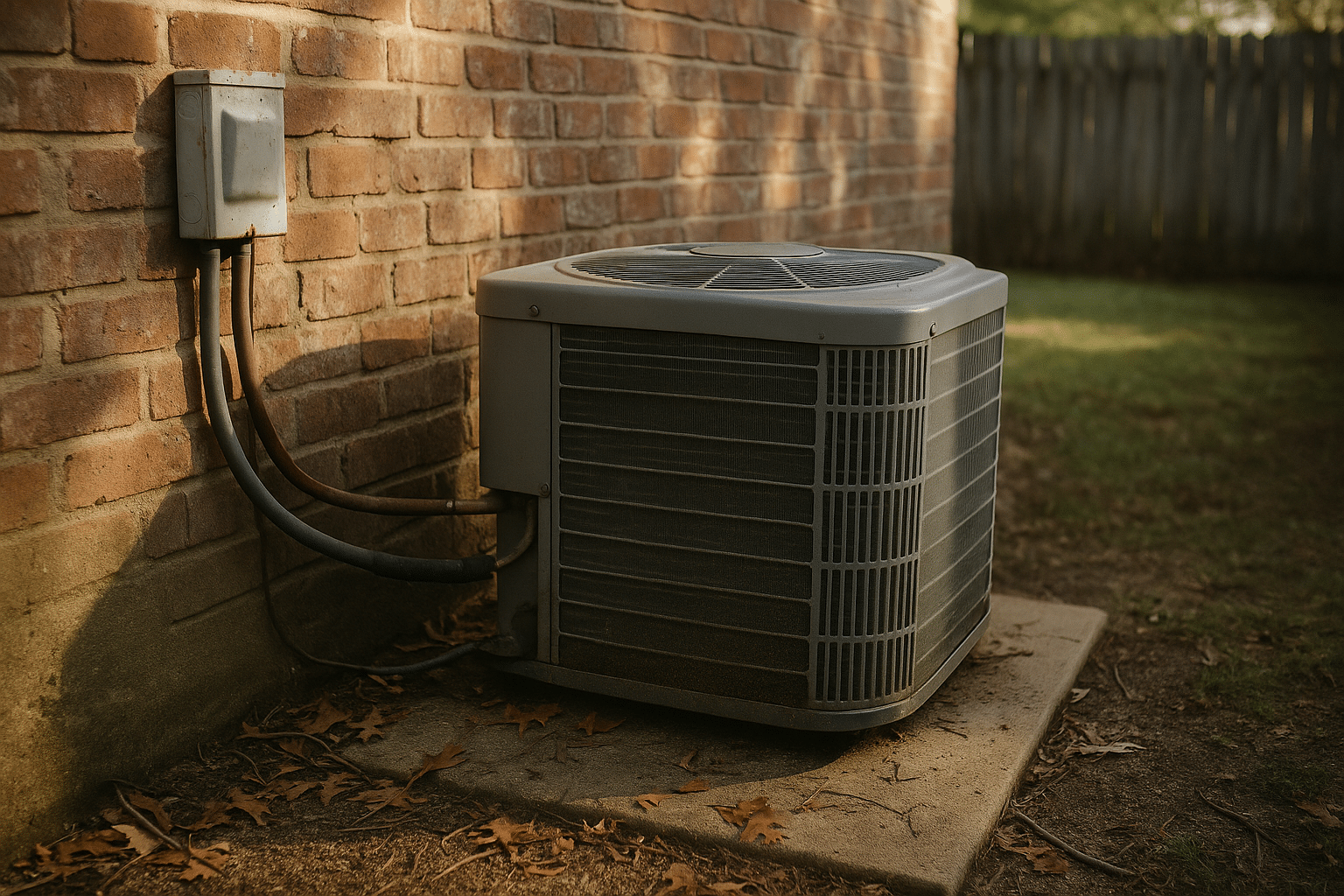

A successful conversion starts with a site assessment. A licensed professional checks space constraints, existing distribution (ducts or radiators), chimney condition, gas availability, and ventilation paths. If a gas main exists on your street, the utility typically verifies capacity and meters an entry point. Where a main is absent, extension timelines and costs can be substantial, and that alone may pause the project. The contractor also reviews heat load—ideally using a standardized calculation—so the new appliance is properly sized. Oversizing is common and leads to short cycling, noise, and lower efficiency in practice.

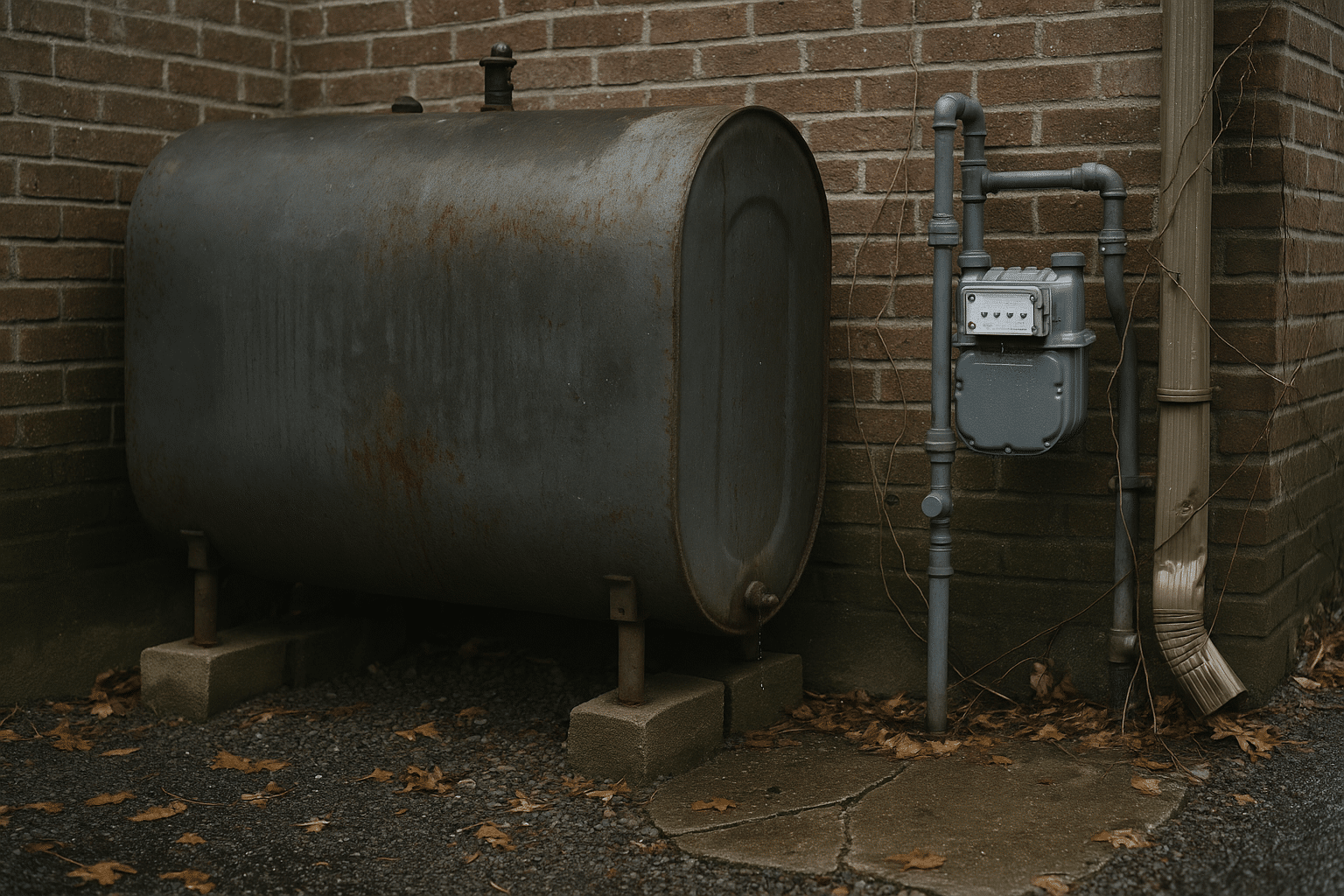

Next comes permitting and safety planning. Gas work requires permits and inspections, and many jurisdictions expect a combustion air calculation, a venting design, and carbon monoxide detectors near sleeping areas and on furnace/boiler levels. If the oil tank remains on site, there are environmental rules for decommissioning. Above-ground tanks are usually pumped, cleaned, and removed; underground tanks often need soil testing and documented closure to prevent liability and contamination risks.

Equipment selection is where choices multiply. For forced-air systems, a gas furnace can provide heating and integrate with existing ducts; for hydronic systems, a gas boiler keeps radiators or in-floor loops in service. Non-condensing units vent to chimneys or metal vents; condensing models extract more heat and typically vent through corrosion-resistant plastic or polypropylene, with a condensate drain to a neutralizer and approved drain. Typical gas service pressure at the appliance is measured in inches of water column—commonly in the single digits—so pipe sizing and pressure drops matter to ensure stable combustion.

Installation proceeds with gas piping from the meter to the appliance, vent routing, electrical connections, and control wiring. Chimney relining may be required to prevent condensation damage and ensure proper draft. Before handoff, a technician should perform combustion analysis, verify manifold pressure, confirm safety shutoffs, and check for leaks using a calibrated detector. A commissioning report documenting CO, CO2, O2, and efficiency readings is valuable; it turns initial setup into a baseline for future maintenance. Expect a typical timeline ranging from a couple of days for a straightforward swap to a few weeks if utility work, chimney relining, or tank removal adds steps.

– Plan permits early to avoid seasonal backlogs

– Request a heat load calculation to prevent oversizing

– Verify venting category and materials before equipment is ordered

– Obtain a written commissioning report with measured combustion data

– Keep all tank-closure paperwork for your records and potential buyers

Efficiency in Practice: Ratings, Controls, and Real-World Performance

Efficiency starts with ratings, but it lives in the details. Older oil boilers and furnaces in the field can operate anywhere from about 60 to 80 percent seasonal efficiency if they lack modern controls or have deferred maintenance. Newer oil units can reach the mid-to-high 80s, though widespread condensing operation is less common due to fuel characteristics. Gas furnaces and boilers range widely: legacy non-condensing models often sit around 80 to 85 percent, while modern condensing equipment is frequently rated in the low-to-high 90s and can approach the upper 90s under favorable return-water or flue conditions. The headline: the appliance choice sets a ceiling, but the home and control strategy determine how close you get to it.

Controls help bridge that gap. Outdoor reset on hydronic systems lowers water temperature when weather is mild, enabling longer, gentler cycles and improved condensing. Modulating burners adjust output to match load, cutting short cycling and reducing standby losses. In ducted systems, sealing and insulating ducts can reclaim a double-digit percentage of heat otherwise lost to attics or crawl spaces. Smart thermostats are helpful, but correct staging and fan settings often matter more than flashy features—gentle ramps can improve comfort and avoid overshoots that waste energy.

To make the numbers tangible, consider energy content and delivered heat. One gallon of No. 2 heating oil contains roughly 138,500 BTU. One therm of natural gas equals 100,000 BTU. Suppose a home uses 800 gallons of oil annually. That’s about 110.8 MMBtu of input energy. At 80 percent seasonal efficiency, the home enjoys around 88.6 MMBtu of delivered heat. To deliver the same output with a condensing gas system running at 95 percent seasonal efficiency, the input would be about 93.3 MMBtu—roughly 933 therms. If local rates and service charges make those therms less expensive than the equivalent oil input, savings follow; if not, the math may favor keeping oil or considering deeper weatherization first.

Maintenance and cleanliness also sway efficiency. Clean filters and strainers, tuned burners, and proper draft reduce soot and keep heat exchangers working as designed. In hydronic systems, balancing radiators, bleeding air, and setting pump curves avoid unnecessary cycling. In ducted systems, a high-efficiency appliance connected to leaky ducts can underperform a modest unit paired with tight, well-insulated runs. The practical takeaway is simple: pursue the appliance upgrade and the system tune together so the rated efficiency shows up on your bill and in your comfort.

– Right-size the appliance using a heat load calculation

– Pair condensing units with low return-water temps to sustain high efficiency

– Seal and insulate ducts; balance hydronic loops

– Use outdoor reset (hydronic) or proper staging (forced air) to curb cycling

– Keep filters clean and schedule annual combustion checks

Sustainability: Emissions, Methane, and the Path to Cleaner Heat

Emissions profiles differ by fuel and by what happens before combustion. On a per-energy basis, widely cited factors place carbon dioxide emissions from natural gas combustion around 117 pounds of CO2 per MMBtu (about 53 kilograms), while distillate fuel oil lands near 161 pounds per MMBtu (roughly 73 kilograms). That means, for the same useful heat delivered, gas typically yields lower direct CO2 emissions than oil, especially when higher-efficiency gas equipment is part of the swap. This is the core climate argument for many conversions: lower carbon intensity per unit energy and higher appliance efficiency combine into a meaningful reduction.

Methane, however, complicates the picture. It is a potent greenhouse gas, with a global warming potential that is much higher than CO2 over a 20-year horizon and still significant over a 100-year period. Upstream leakage during production and distribution can narrow or, in some settings, offset the combustion advantage. The practical implication is not to abandon conversion outright, but to view it in context: local leakage rates, utility improvement programs, and the choice of high-efficiency equipment all matter. Asking your utility about measured leak rates and planned infrastructure upgrades is reasonable and increasingly common among conscientious customers.

Local air quality considerations also enter the sustainability conversation. Modern appliances with low-NOx burners and verified combustion can reduce certain pollutants relative to older equipment. Proper venting and draft, combined with regular maintenance, help prevent soot or CO formation. Inside the home, sealed combustion and good ventilation limit exposure to byproducts and improve safety—a sustainability factor too often overlooked in favor of purely carbon metrics.

Future-proofing is a strategic layer. Some gas utilities are piloting modest blends of renewable natural gas, and research into hydrogen blending exists, though practical limits, appliance compatibility, and infrastructure considerations make high-percentage blends complicated today. Meanwhile, investments in the building shell—air sealing, insulation, window improvements—reduce the size of any future heating system, whether it’s gas, a hybrid setup, or a heat pump. Planning for an electrical subpanel upgrade and a condensate drain can keep pathways open for later electrification, if that aligns with your long-term goals.

– Combustion CO2 factors: gas ~117 lb/MMBtu; oil ~161 lb/MMBtu

– Methane leakage is a key uncertainty; ask about local utility efforts

– Sealed combustion and low-NOx designs can improve indoor and outdoor air quality

– Weatherization strengthens any fuel choice and supports future transitions

– Keep documentation of commissioning for safety and efficiency verification

Conclusion and Decision Checklist: Costs, Incentives, and Next Steps

Numbers drive confidence, so frame the decision with a simple structure. Total project cost includes equipment, labor, venting or chimney relining, gas piping, meter work or main extension if needed, oil tank removal and soil testing where applicable, permits, and optional controls or duct/hydronic upgrades. Annual operating costs combine fuel price, fixed service charges, estimated consumption based on a heat load and seasonal efficiency, and maintenance. Incentives—utility rebates, regional energy-efficiency programs, and occasional tax credits—can narrow the upfront gap. Financing terms and interest matter too, especially if you evaluate payback versus a loan amortization schedule.

You can run a back-of-the-envelope comparison with a few inputs. Estimate your delivered heat need from historical oil consumption. Convert gallons to BTU and adjust for existing seasonal efficiency to find delivered MMBtu. Choose a realistic seasonal efficiency for the gas equipment under your home’s conditions. Convert delivered heat back to gas input (MMBtu) and to therms. Multiply by local rates and add fixed charges to get an annual cost estimate. Include maintenance differentials and expected lifespan to compare lifecycle cost rather than only first-year savings. This is not perfect, but it is far more informative than relying on nameplate ratings alone.

Beyond math, practical comfort and risk reduction matter. No more oil deliveries can mean fewer scheduling hassles and less chance of spills. On the other hand, gas availability, potential main-extension delays, and the responsibility to manage combustion safety and carbon monoxide alarms come with the territory. If a major weatherization project is on your horizon, doing it before or alongside the conversion may let you select a smaller, quieter appliance. And if your long-term plan includes partial or full electrification, choose controls and a panel configuration that make a later transition straightforward.

Use this checklist to close the loop:

– Request a formal heat load calculation and a detailed scope of work

– Ask for line-item pricing: equipment, venting, piping, permits, and tank work

– Get commissioning targets in writing and a copy of measured results after startup

– Compare annualized costs using your actual fuel history and local rates

– Confirm incentives, timelines, inspections, and warranty coverage

– Plan for weatherization and future electrical needs while walls are open

In short, oil-to-gas conversion can enhance efficiency, reduce direct CO2 emissions, and simplify fuel logistics, provided the project is sized well, installed cleanly, and paired with sensible controls. Treat the decision as a system upgrade rather than a single-box swap, and you’ll be positioned to capture the advantages today while keeping options open for tomorrow.